The Service Design Award is currently open for submission again. Submit your project for a chance to win and present at the Service Design Global Conference in Toronto this year.

Kraftens hus (House of power)

Social innovation design by, for and with cancer-affected

Summary

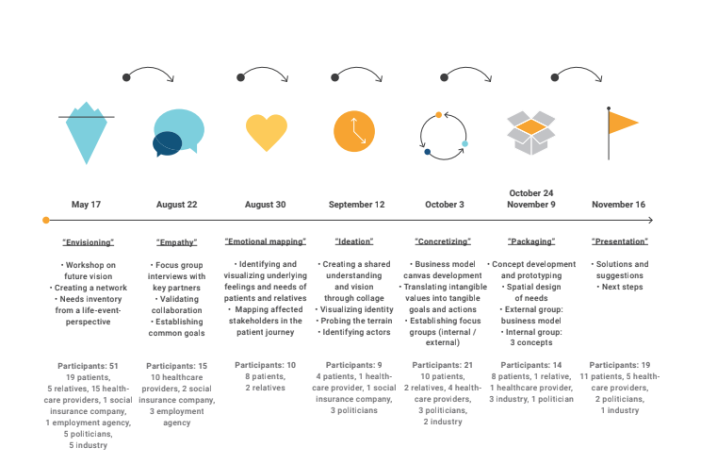

“Kraftens Hus” is a social innovation project based in Sweden designed by, for and with cancer-affected. A collective user-driven design work led by a service designer has resulted in the establishment of a sustainable NGO, an open meeting place and a new way of working for the involved parts.

Introduction

One in three people in Sweden will be diagnosed with cancer during their lifetime, and almost 40 percent of these are children or people of working age. Meanwhile, better treatment and earlier detection mean that more people are living longer with the disease (Socialstyrelsen and Cancerfonden, 2013). However, life is changing on many levels after a cancer diagnosis.

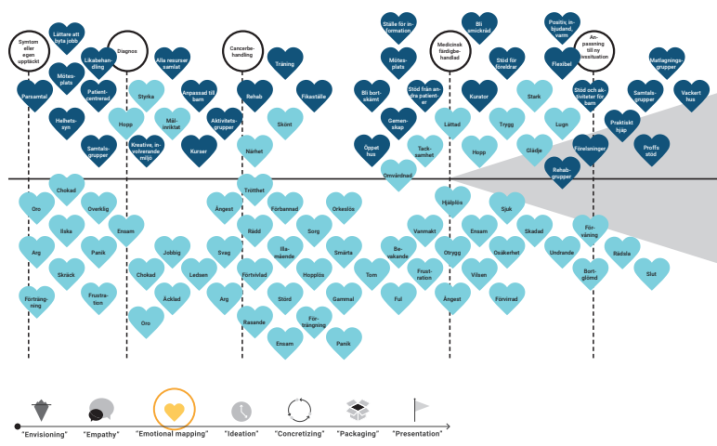

A cancer diagnosis affects a person physically, mentally, and socially. Returning to a well-functioning life after cancer requires rehabilitation and cooperation between many different organizations in a person’s ecosystem both private and public, such as healthcare providers, social insurance company, employment agency, employers, schools, etc. However, cancer patients and relatives often experience psychosocial support as insufficient – both during and after treatment (Olsson, 2016).

Without such support, finding one’s new identity and way back to everyday life is difficult. In addition, the risk for relatives to fall sick due to stress caused by the disease increases by 25 percent one year after the diagnosis (Sjövall, 2011). Not only does a cancer diagnosis affect patients and relatives, but also colleagues at work, healthcare providers, social insurance agency, employers, school, etc. The social welfare system alone will not be able to tackle this challenge. Therefore, we need to think in new paths about how public and private resources can be integrated better to provide support for cancer-affected, in a holistic way. In this innovative design project, the gaps between the involved stakeholders in a cancer patient’s rehabilitation journey were identified and all of the actors were invited to participate in a collaborative service design project with the aim to design better-integrated solutions beneficial for both cancer-affected and all stakeholders.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment