The Service Design Award is currently open for submission again. Submit your project for a chance to win and present at the Service Design Global Conference in Toronto this year.

Introduction

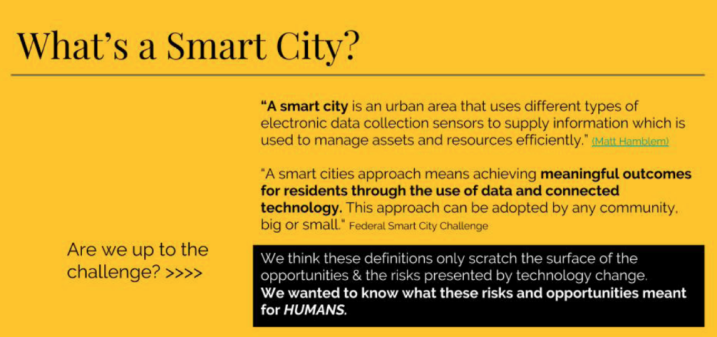

In 2017, the Federal Government announced a funding opportunity for municipalities related to Smart Cities. As our municipality considered a bid, the dominant question being asked was: What can technology offer the city? An internal client approached our innovation lab and asked a more difficult question that framed the challenge for this project: How could we ensure we were thinking about not just a technology and data-enabled city, but also a smart city that worked for people?

“The city is its people. We don’t make cities in order to make buildings and infrastructure. We make cities in order to come together, to create wealth, culture, more people. As social animals, we create the city to be with other people, to work, live, play. Buildings, vehicles, and infrastructure are mere enablers, not drivers. They are a side-effect, a by-product, of people and culture. Of choosing the city.”

- Dan Hill, City of Sound, 2013

To understand that shift, we considered this question: Why do we build cities? What is their core purpose?

In our context, the Smart Cities discussion primarily focused on outcomes such as efficiency through technology. Our internal client challenged our team to help the municipal government understand how we might reconcile the city’s core reason for being (bringing

people together to have a good life) against the changes technology can initiate.

Objectives

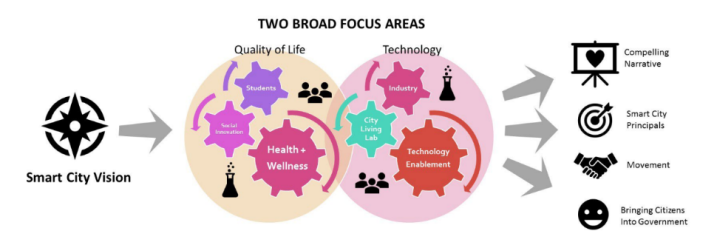

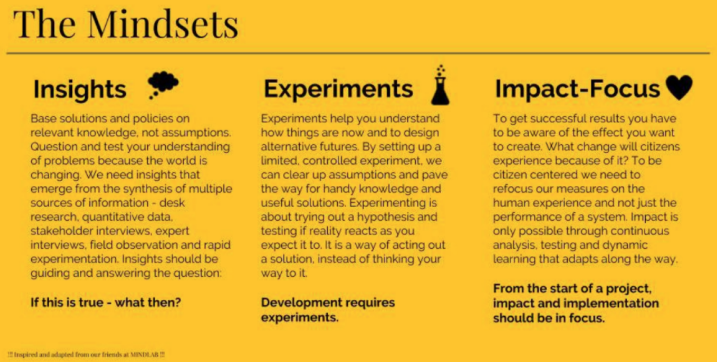

For our team, exploring this challenge meant applying traditional and non-traditional service design methodologies including advanced analytics, strategic foresight and human-centered design approaches to the problem. We named this sprint “Dark Matter,” and its objectives were:

- Demonstrate what can be achieved when a service design mindset is brought into government.

- Leverage insights from human-centered and digital data sources to understand trends, opportunities and develop future scenarios.

- Work with internal and external stakeholders to design immersive experiments to bring those future scenarios to life.

- Develop and deepen formal and informal channels for staff to work cross-corporately, partner with the community, and take smart

risks. - Produce an artifact that captured the insights generated through this work. This took the form of a Smart Cities, Made Human playbook and a narrative showcasing the city’s ability to think and work in a new way.

Audience

The target audiences for our work included civil servants at the municipal level, civic institutions, universities, community agencies, and the residents of our city.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment