Customer experience and the gap

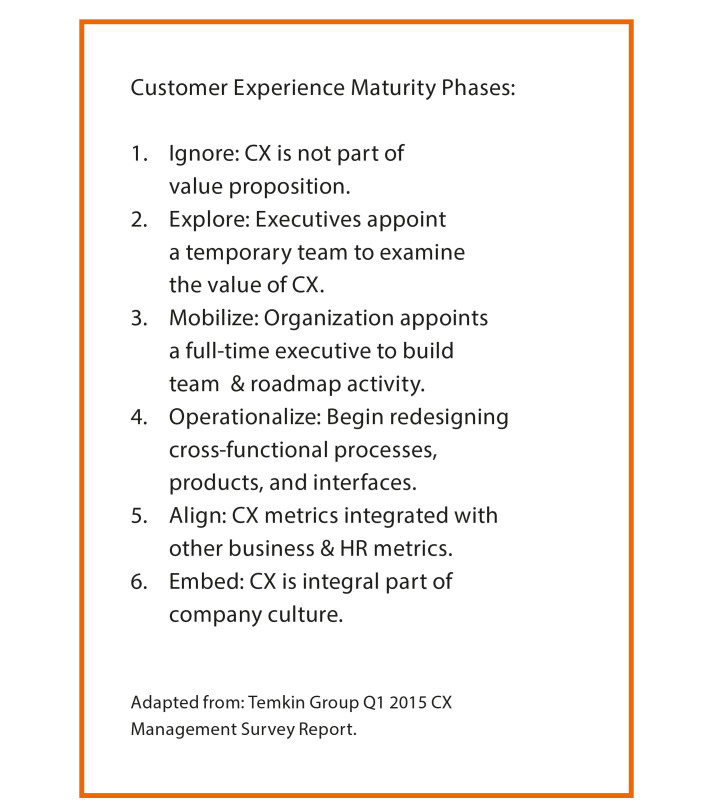

CX as a discipline and strategic approach gained both visibility and practitioners over the last 15 years, with faster movement over the past eight-to-ten years. CX is now visible in the C-suite of many large companies and a ‘commitment’ to improving customer experiences (and patient experiences, and student experiences, etc.) appears in many mission and strategy statements.

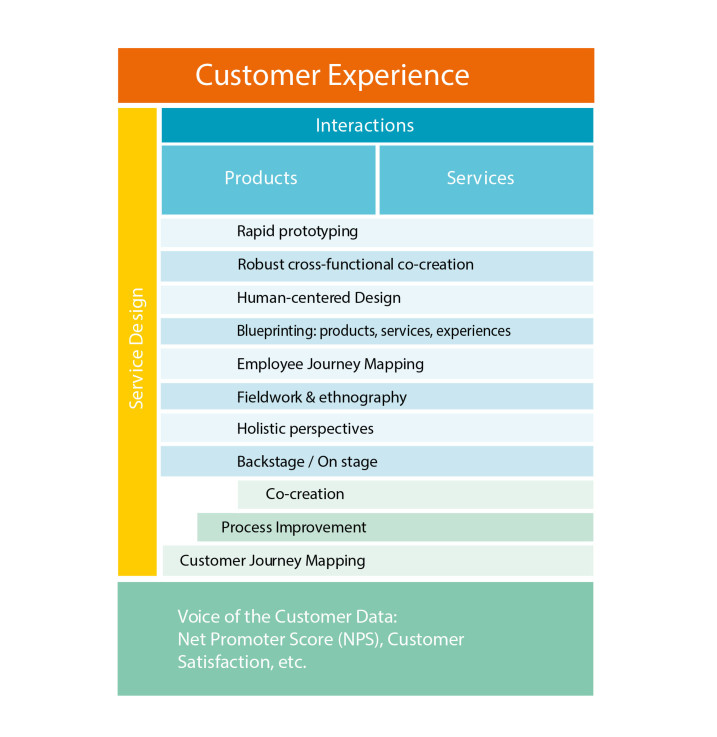

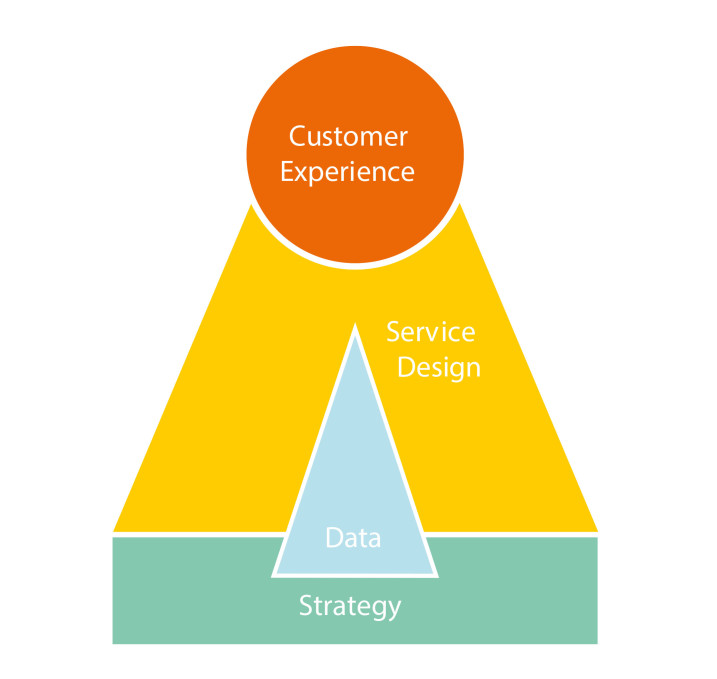

CX is a strategic perspective and value proposition that seeks to deliver customer retention and brand differentiation. Unfortunately, CX currently struggles with an identity crisis and a failure to fully deliver on its promise. As we will explore below, the penchant of customer experience leaders to focuson numbers and measurements without framing to actually design the necessary changes has created a gap that service design is ready to fill.

While CX leaders across industries agree on the goal of their efforts, i.e. ‘We need to improve customer experience in order to improve loyalty and revenue,’ there seems to be no agreement on crucial points to secure progress and success. Basic questions abound: how do we define ‘customer experience'?; who owns customer experience?; and just how do we actually improve it?

Disparities of definition exist across industries, within individual organisations and across the professional practice of CX itself. If business leaders and service designers are confused about exactly what CX is, it’s due to the fact that, within the discipline itself, there is very little that is unified or consistent.

CX as customer service

For some organisations, CX walked through the door as a process improvement approach (or sometimes merely a new name) for customer service: the part of an organisation that customers encounter as they learn to use its products or when something goes wrong. This continues to be a very common approach as even more companies begin their CX journeys. Many CX jobs posted on LinkedIn in the US are actually customer service jobs with a new label. For example, Comcast's 2015 announcement that it was hiring 5000 CX specialists didn't mean hiring 5000 analysts, designers or ethnographers, but rather more service agents, call centre agents and installers who would now be called customer experience agents.

Historically, early customer experience efforts focused on improving customer service because, in many industries, it is the most visible interface with the company. It's not a bad place to start, but a number of companies stop there, and customer service is far from a finishing point.

Measuring: Net Promoter Score

Before many organisations are willing to establish an internal program for CX, they want to make sure they have measurements in place to determine the effectiveness of their efforts. The approaches to finding the right measure(s) have been many and varied.

Fred Reicheld’s work regarding customer loyalty led to the concept of the Net Promoter Score (NPS): a measure of customers' likelihood to recommend the company or its products and services to friends and family members. The value proposition behind the NPS is its promise to be the highest correlative indicator of customer loyalty and word-of-mouth recommendation.1

In theory, improvements in NPS will improve customer retention and net revenues. In practice, NPS strategy and implementation have been, for many companies, a confusing breakdown point. Where does NPS fit in the company? What does it actually mean? How does one use it to make actual improvements? Every business has a different response to each question, and most combinations leave CX programs that are struggling to demonstrate their promise.

Measuring: Voice of the Customer

A number of organisations approach CX as primarily a ‘listening’ post activity and equate it with Voice of the Customer (VOC). That is why, in many companies, marketing and VOC programs were the first to champion a concept of CX, seeing it as another way to measure customer satisfaction.

For these companies, the introduction of CX and NPS happened in relation to market evaluation and analysis. For some, this was as far as they got. The good news is that CX leaders are beginning to recognize the shortcomings of these current systems.

Journey-mapping & process design

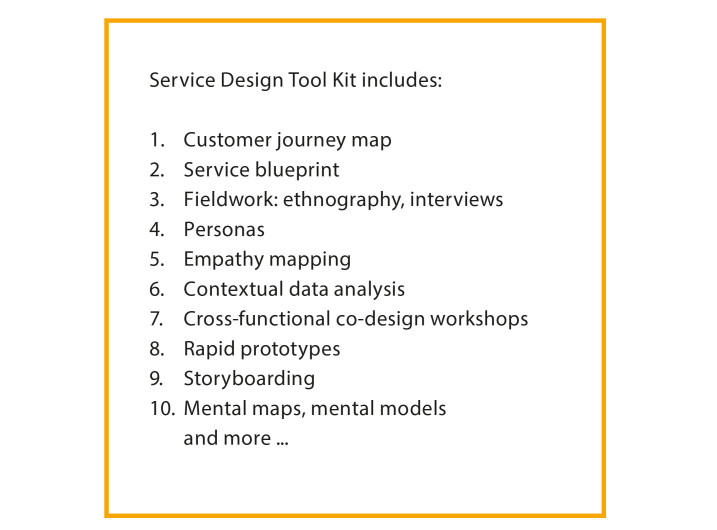

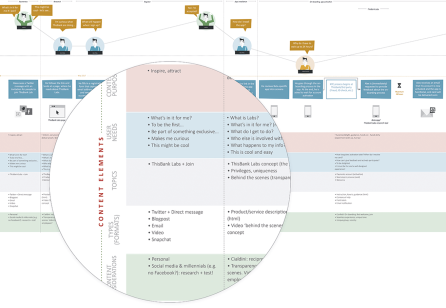

Frustrated CX leaders are looking for other approaches to link data insights to customer insights in order to execute on real innovation. Many CX programs have begun to use one particular service design technique: the journey map. It is the tool of choice for clarifying and examining pain points, and often leads to first attempts at co-design efforts (though most CX leaders don't choose the word ‘design’).

Too many times, journey mapping and first efforts at co-design don't get very far. A core reason for this shortfall is the tendency of business to work from the inside out: accepting perceived limitations and internal untouchable traditions as the starting point (rather than questioning them and re-evaluating reality). We also see resistance to new methods of problem-solving. Making real differences to the products, services and systems that create the customer experience requires intentional change. Despite protests to the contrary, few organisations really like change.

We are reaching a tipping point: CX leaders now see the gap between their measurements and the goals that they have set for themselves. Customer experience leaders grow more willing to consider alternatives.2

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment