Service Design At A Crossroads

A management consultant, a designer and a cultural anthropologist go into a bar for a drink.

Browse all Touchpoint Articles

A management consultant, a designer and a cultural anthropologist go into a bar for a drink.

A hands-on workshop about co-research methods and tools adapted to a young target group

The splendid view from the Microsoft New England Research and Development Building framed the Service Design Conference opening reception on October 27th in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sometimes Service Designers encounter projects where the client organisation is new to Service Design, maybe even to the extent that the client does not recognise that they need Service Design.

»Sarah Drummond inspired a group of talented strangers to rally around her seemingly crazy idea of making a prototype and presenting it to a panel of investors at Social Innovation Camp.

The design challenge encouraged participants to reflect on their own Service Design journey.

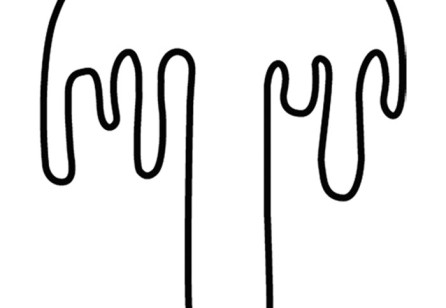

How and Where to Start? – How do you wow the customer in today’s ever-changing world?

Earlier this year, members of the Service Design Thematic Commission began an open discussion about the evaluation of Service-Design projects(...)

Wyndford is a community in the North West of Glasgow and is ranked the 18th most deprived area in Scotland. Until last September, they had never met designers before.

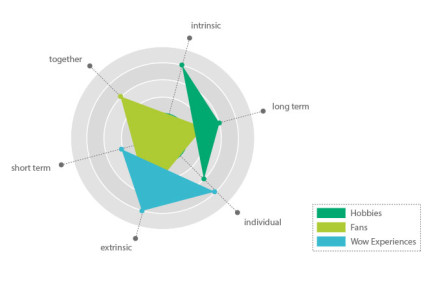

»We want to enthuse our customer« is a phrase a Service Designer hears quite often. Most companies who strive for this do not know that they are treading on hallowed ground.

In financially uncertain times such as these, navigating a clear road to service delivery is increasingly challenging.

The cloud might be a little frightening: it’s invisible, all-consuming and, scariest of all, it’s telling you that your business needs to change.

Many years ago, life was simple. Everyone had only one name, one phone number, one address and one set of keys.

The project was a purely online, collaborative project concerned with rethinking higher education.

A few weeks before the conference, Minka, who runs the Service Design Network office, came into our workplace with a smile.

These practitioners tend in their everyday practice to adopt product service system thinking and to build extended design offerings.