OUTPUT

Contents

So what should this resource contain? I just listened to the project group.. They know better how to apply these findings than I do. That’s why the material is presented this way. It is intended to create as much value for the Center for Development as possible. It’s meant to be actionable, informative, and engaging, but also universal enough that it could apply to many homes, long and short term, publicly or privately run.

They had specifically said the timelines were very helpful to be able to point to certain patterns and flows. I included the timelines and general findings in a Background section. They also wanted to include the charts that illustrated specific percentages, which I expected. One illustration that I put in for fun, to give the piece some levity, showed all the parts a staff member needs to complete their work. It included items like a stomach that never hungers, and a throat that doesn’t thirst. It was a play on a quote from an interview, saying “to work here, you need a cold brain, warm heart, soft hands, and strong legs.” I thought that sentiment was beautiful, but lacking a bit. They appreciated my humor and wanted this illustration included.

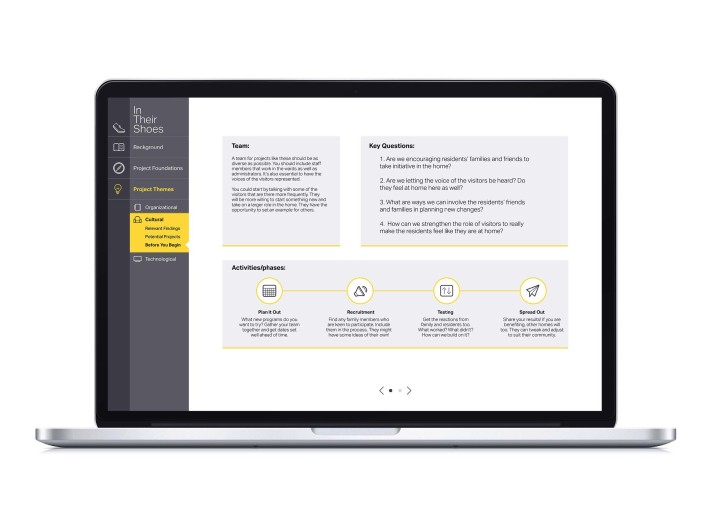

I included it with the more detailed findings under three Project Themes. These themes were technology, culture, organization. I filled these themes with the most relevant findings, as well as tips on how to go about building a project within one of these themes. I looked back to my work with grant projects at the Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation. I knew that certain questions would help a team kick off the project in the right direction and build momentum. The goal is to communicate, with as much detail as possible, what it’s really like to work in a nursing home, and what you need to consider to start a new project. Really, it’s imploring the user to look closer at things they think they know. It hopes to keep the voice of those caring for our aging family members relevant and available. It isn’t meant to be a “Well we read this, so now we’re all set on research.” But rather, a good place to start. If this resource leaves its readers with more questions than answers, it’s done its job.

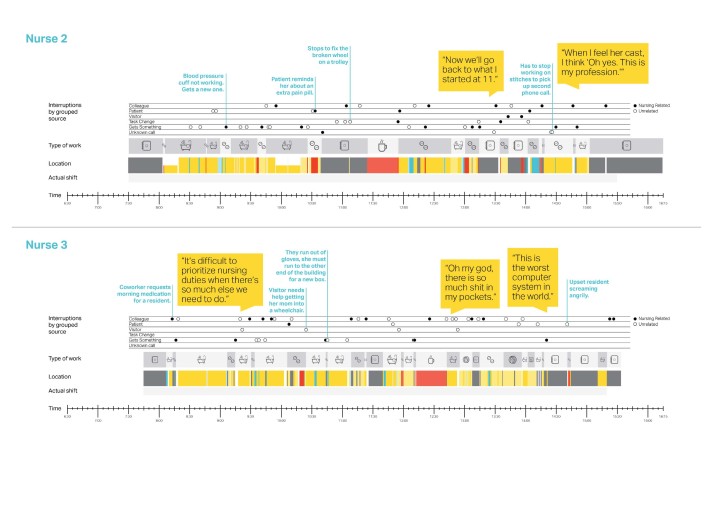

The project team also wanted to include the direct quotes from staff and patients. Those brought a human quality to the numbers. This softer side also inspired what is, for me, the most important section of this resource. I noticed that there were larger principles emerging. These were obvious, painfully so at times, but necessary to include.

The Project Foundations are five statements that capture a set of reminders. They’re too simple to be principles. Besides, they aren’t rules, they’re requests. Written from the perspective of the staff, they are simple requests to remember the basics of being in a home. My personal favorite, “Remember that there are only 60 minutes in each hour.” is a reminder that time is finite. Anything that gets added to the staff to-do list means that something else is bumped off. The days are packed, and unless time is freed up, new responsibilities won’t have a place to fit in, no matter how valid they may be. The Foundations serve as a way to ground future projects. These things frequently get forgotten, when they really are so central to the way any nursing home operates.

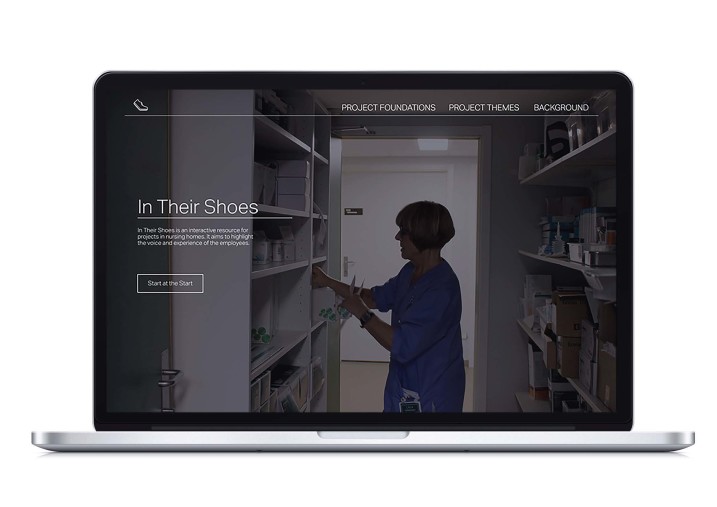

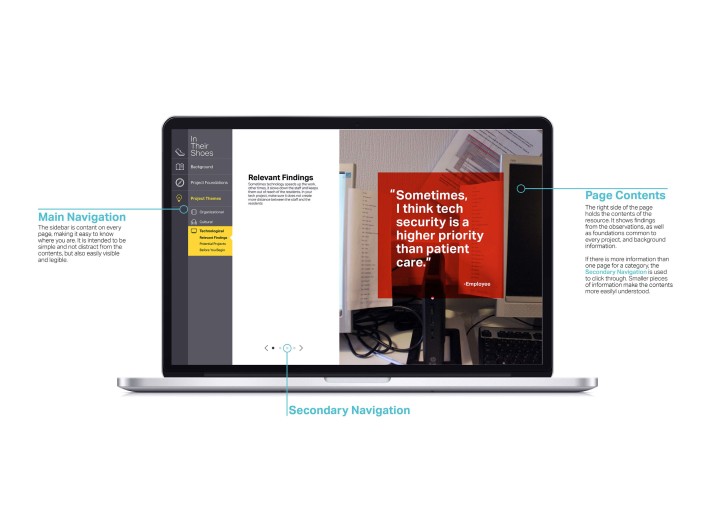

Form

So I knew what I needed to include, but what would it look like? It would be digital for sure, so that it was easily shareable. But I had only a few weeks left in the project to build the final version, so it had to be quick. I didn’t want to make it one long document that you had to scroll through. I wanted it to be possible to get the information you needed right away, but also explore and find new things as well.

Making it interactive was a way to encourage exploration and keep the information from being too overwhelming.

I decided to make an interactive PDF because it fit all the requirements. Users could click through to find what they needed, while avoiding extra information that might not be relevant. Team members could bookmark certain pages or add comments to particularly relevant findings. A PDF is also a format that everyone can open and read, without having to install specialized software or worry about font compatibility. The final file size, at 3.5MB, was well within email attachment restrictions, making it shareable. Most importantly, I knew I could make it with the time left in the semester.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment