Social Issue

Children and young people are taken into care because they are considered to be in a vulnerable situation. For example they may have experienced neglect, mental, physical or emotional abuse, or their parents may have died or become unable to care for them any longer1. The majority of young people in Scotland leave the care service aged 16 years2 (in contrast to the average age of leaving home of 22 in the wider population3) and report feeling pushed to leave before they are ready4.

Unfortunately young people with care experience feature prominently in statistics about vulnerable young adults; most worrying is that around one third of people who are homeless have lived in care5. There is a grave irony that a state that takes young people into its care because they are vulnerable becomes a parent to homeless young adults.

Leaving Care Service

In 2004 each of the 32 local authorities in Scotland were required to create leaving care services (LCSs) which are specialised social work service that has a legal duty to support young people as they leave care. One of the responsibilities of leaving care workers (LCW) is to ensure care leavers have somewhere to live.

A literature review6 about LCSs in Scotland did not provide evidence about how LCWs currently provide support to access housing or people’s experience of this service provision. What was known was that young people reported being illprepared and unsupported as they left care7, and practitioners stated that they found this transition difficult to support8.

Service Design Focus

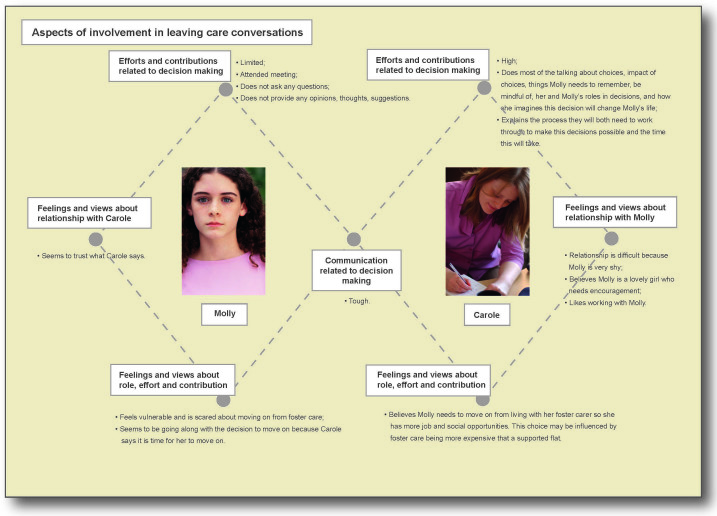

Meroni and Sangiorgi propose four ways to think about service design9. One of these approaches is to design for people’s interactions, relationships and experiences. Effective LCS provision relies on the quality of the relationship between young people and their LCWs, and good communication10. If this relationships and communication is poor it can be difficult for young people to understand and remember the accommodation that is on offer to them as they leave care. This may contribute to them experiencing homelessness. This submission therefore focused upon conversations about where a young person may live as they leave care.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment