Shifting mindsets through storytelling and sense-making

Over the course of two days, workshop participants engaged in deep and meaningful dialogues, as well as mapped challenges and opportunities for policy implementation. Workshop capacity was limited to 14 public servants to ensure intimate and effective conversations. At the end of the second day, teams pitched ideas to a leadership panel. Below are some of the methods used by our team to guide public servants through a systemic design process.

Sharing stories together

Engaging in dialogue with gender-diverse communities was key to understanding how the policy impacts people and why building inclusive services is so important. This was a transformational part of the workshop because for many participants in the room, it was their first time hearing first-hand experiences from trans, non-binary, two-spirt and gender-fluid individuals. To create a safe and welcoming environment, facilitators met with ‘Inclusive Dialogue’ guests prior to the workshop to answer questions and consider any needs they may have.

Seating was arranged in a circle and guests were given the floor to share their story, before opening the dialogue for questions. We tried our best to include more than one guest in our dialogue to share different perspectives, as well as to avoid putting the spotlight on an individual. The session was hosted after a lunch break where participants and dialogue guests had a chance to meet informally over a meal.

Before the ‘Inclusive Dialogue’, we had a chance to hear from participants where they see challenges, opportunities and interdependencies for implementation. Giving participants the chance to share their frustrations before the ‘Inclusive Dialogue’ was key to ensuring participants felt heard and were ready to listen to guests with an open mind.

Visualising what we heard

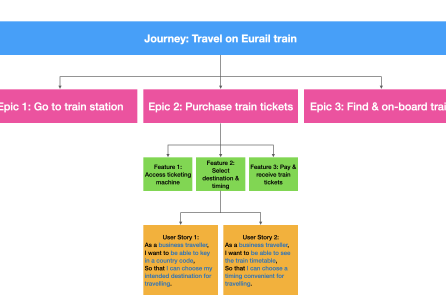

Mapping exercises were introduced to support participants in making sense of what they learned from stories shared throughout the day. A hybrid of design and systems thinking tools were used to map both client needs, as well as interdependencies. For example, personas and journey maps helped to identify client pain-points, while influence maps helped to identify key actors in the system and how they influence one another. By the end of the first day, participants had a chance to vote on the key challenges that were the most crucial to focus on.

Letting go of the expert hat

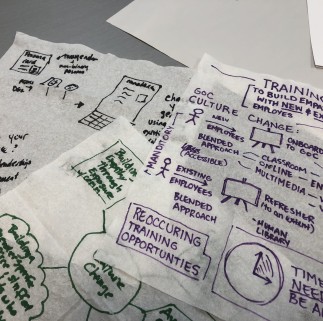

Three key challenges were identified, and interdisciplinary teams were formed. Participants were encouraged to let go of their ‘expert hats’ by joining a challenge they were less familiar with. A series of brainstorming exercises were introduced to encourage divergence and play, such as using analogies, drawing on napkins and referring to cards with idea prompts.

The workshops concluded with participants pitching ideas to a leadership panel. The opportunity to present to a leadership panel was important, because participants had a chance to hear feedback directly on what they need to consider as they move forward with implementation. Leaders also had a chance to be exposed to this approach and their participation gave legitimacy to the workshops.

Fostering a community of practice

After the workshop, participants expressed a desire to connect with other workshop participants. They were very curious about other workshops and what challenges other services were facing. Our gender-diverse guests were also eager to stay involved in the work and learn about the progress departments were making. Therefore, we launched a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991)2 to continue connecting people and sustain implementation.

A toolkit that shares methods and findings from our nine workshops is in development and aims to empower participants to become ambassadors of the policy direction in their own organisations. Our hope is that this becomes a self-sustaining, dedicated community that continues to implement the policy direction long after our team ceases to exist.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment