What is innovation?

For the City of Ottawa, Canada’s national capital, it started with a single (but far from simple) question: How do we embed innovation into the organisation, across every department?

What’s interesting about this particular question is its perspective. So much of what we see in municipal innovation tends to be focused on external initiatives, such as creating better places for people to live, work, play and visit. These initiatives include research and investment in Smart Cities activities, policies and programmes to attract government and private sector investment, building start-up communities and public/private partnerships. These are all critical initiatives, but they often require significant investment and partnerships. Rarely do we see cities reflect on what’s required to build an innovative city from the inside out, looking internally at what’s required as an organisation to enable employees to create those external innovation initiatives at the grassroots level.

With the support of the senior management team, and under the leadership of the Director of Service Transformation, Marc Ren. de Cotret, PwC and the City of Ottawa partnered to answer the question that was posed, and understand how the city could embed, support, and empower innovation across all of its services and departments – starting from the inside.

From the outset, Marc understood the importance of clearly defining what innovation meant for the Ottawa. It meant building a unique definition of what innovation means in the public sector, within the city’s own organisation and operating model constraints, while at the same time keeping focus on delivering real results for ‘clients’ (the city’s term for a diverse group of end users, including residents, businesses, visitors, partners, etc.).

This meant moving beyond a theoretical exercise or falling back upon stereotypical innovation examples from Silicon Valley and tech start-ups. As Marc put it, “we’re not going to be developing the next iPhone at the City. Nor should we be measuring ourselves against that kind of innovation. If you’re a service delivery organisation, in a public sector environment, in a municipal setting, how do you define innovation that makes it something that’s real and tangible that can be incorporated into the way you deliver services to citizens?”

Why an Innovation Operating Model?

The city had a very clear need to identify actionable, implementable changes to its internal processes, operating model and culture in order to enable what it called ‘innovation at the edges’. This means innovation that happens closest to the point of service, empowering employees who are interacting with clients to identify the need for something to change, and then going out and changing it.

“At our core, Ottawa (like any city) is a service delivery organisation,” said Marc. “And like any service delivery organisation, we need to find a way to keep pace with changing client expectations that are driving towards more and more personalised, customised, and in-context service experiences. In order to be able to keep up with that pace of change, we have to extend our ability to innovate, in our organisation.”

With our goal of delivering exceptional client service through grassroots innovation, we needed to understand what processes, systems and cultural factors were acting as enablers of – and barriers to – this innovation ‘at the edges’. Why was innovation happening in certain pockets of the organisation, but not in others? What was making service transformation possible sometimes, but not always? Was there truly a recipe for success that we could formalise, replicate, and embed across the organisation?

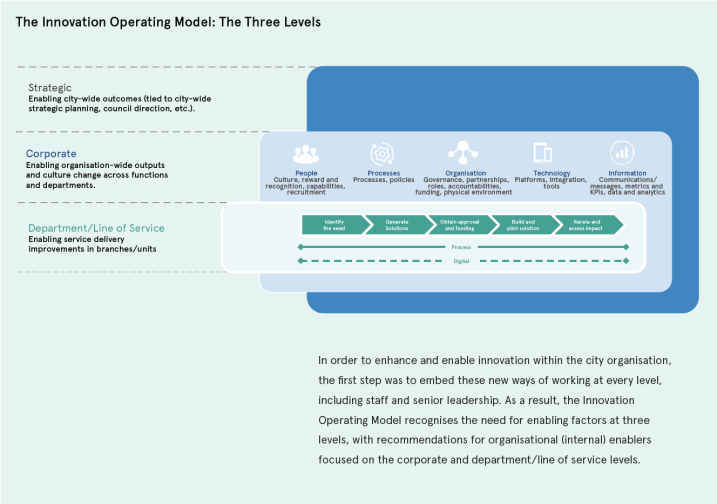

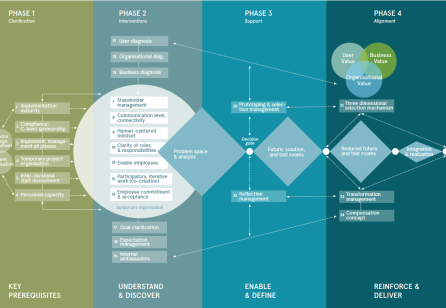

With these questions simmering in our minds, PwC and the City of Ottawa embarked on a four-month service design journey to define a new innovation operating model. The goal of the operating model was to go beyond simply creating a ‘culture of innovation’. The choice of an operating model was deliberate, because both the city and PwC understood that for a culture of innovation to be sustainable, innovation enablers must be defined and embedded into core operating principles, touching upon data and analytics, IT systems, governance, people skills, individual development plans and more. All the individual components of an supoperating model needed to work together to create an ecosystem of support for innovation internally.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment