Introduction

After almost a century, and several failed attempts to establish a coherent rural land identification and registration system across the whole of Portugal; a cooperative initiative between different Government sectors was created in 2017. This initiative had one goal: to finally understand who owns what, and where.

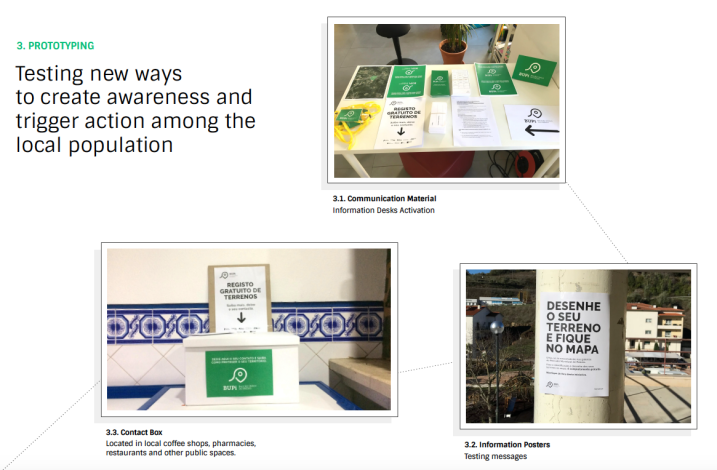

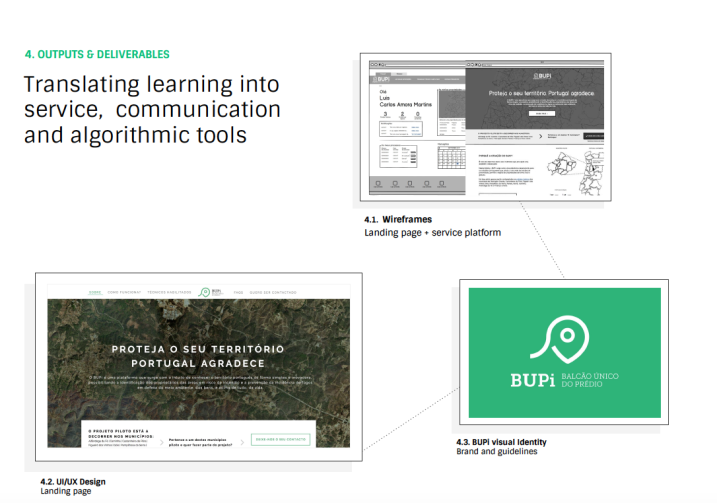

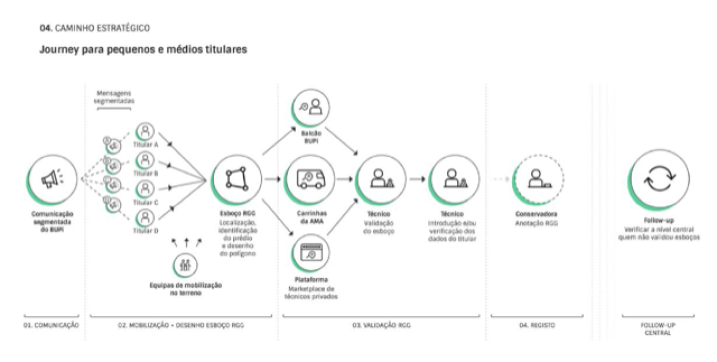

In order to test a new approach, a pilot-project targeting 10 municipalities in the interior region of Portugal was created. Its goal was to mobilize rural property owners to identify the location and limits of their properties on a digital map, based on satellite images , at local information desks and with the help of specialized technicians. Our role was to design the entire experience of this public service and define the mobilization strategy, with the goal of mapping more than 50% of the combined territory across these 10 locations.

Process

Through a Service Design approach, we immersed ourselves in this context by re-locating ourselves to one of the municipalities, listening carefully, exploring the lands, engaging stakeholders and putting the users and client at the centre of the project. We set up a dedicated team of distinctive brains (Researcher, Creative Strategist, Strategist, Digital

Designer and a Multidisciplinary Designer) and engaged the remaining project partners to create the conditions to generate good ideas and outcomes.

Research

We used qualitative and ethnographic research methods as a way to explore the problem from different perspectives. We did in-depth interviews, to learn about the origins, the stories and the relationships people have with their lands. We made participatory and non-participatory observations, to see how people actually manage and define the limits of their lands and also learn about how they experienced the service. We did context immersion , by putting ourselves into a land identification and registry process, where we even tried to buy an 11,572m 2 property. We used mobile ethnography, to self-document the experience. We facilitated co-creation sessions, to involve and generate commitment from local stakeholders and ultimately, we role-played and prototyped for empathy, to learn and test different scenarios, experiences and approaches to the population.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment