The Norwegian innovation lab for public sector: StimuLab

StimuLab is a learning platform for public innovation that supports and encourages user-oriented experimentation and innovation, using a design methodology. With funding of €6 million from 2016-2020, it has at present supported 29 projects.

StimuLab was initiated by the Norwegian government in 2016 and is run as a collaboration between Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA) and the Norwegian Digitalization Agency, which represents a unique cooperation.

From ‘Double’ to ‘Triple’ diamond

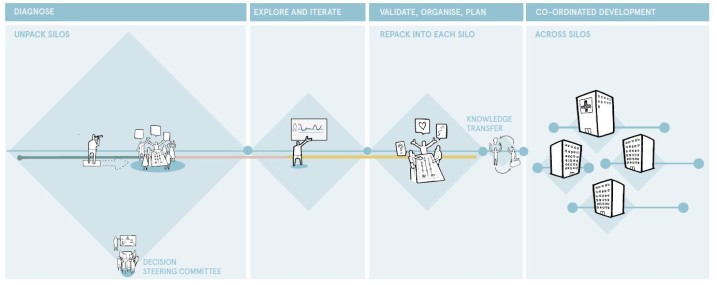

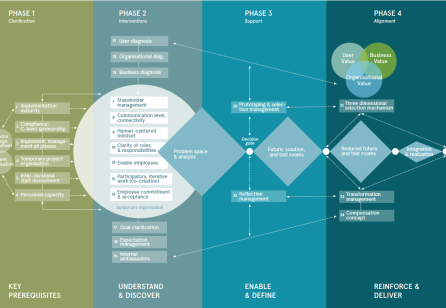

Projects supported by StimuLab must commit to following the ‘Triple Diamond’. As this model from Halogen shows, iteration and adaptation are essential when meeting the needs of highly complex projects. Source: StimuLab / Halogen

At the core of StimuLab is service design. Building on the UK Design Council's Double Diamond2, we added a third, and made the ‘Triple Diamond’ a mandatory framework for all StimuLab projects. The new diamond, the diagnose phase, emphasises how important it is to truly explore and understand root causes hidden in complex public issues. When faced with cross-sectorial challenges, it is crucial to create a shared understanding of problems and needs, at several levels, simultaneously – from users to services to systems and back – across sectors and by involving all stakeholders.

Out-of-house lab

Numerous countries have established in-house government innovation labs to provide expertise and drive development. But because the Norwegian supplier market is highly-skilled, StimuLab strategically chose not to create an in-house lab, but instead to procure services from the market to develop and deliver solutions together with public organisations.

Tailored skill configuration

Furthermore, each StimuLab project demands a tailored skill configuration from the market, for example, impact assessment, data analysis or behavioural psychology, to strengthen its capacity to deal with the domain at hand and to handle areas of complexity.

These matching skill configurations are not typically something that design consultants are able to deliver. So, to meet these demands, they initiate formal collaborations with e.g. management consultancies, who provide necessary, complementary expertise. As a result, StimuLab has been a catalyst for new co-operation and knowledge development to solve challenges that the Norwegian public sector has been unable to address so far. By offering increasingly complex projects to the market, StimuLab has also helped make the public sector an attractive client for a growing supplier market.

Charting low or high levels of complexity

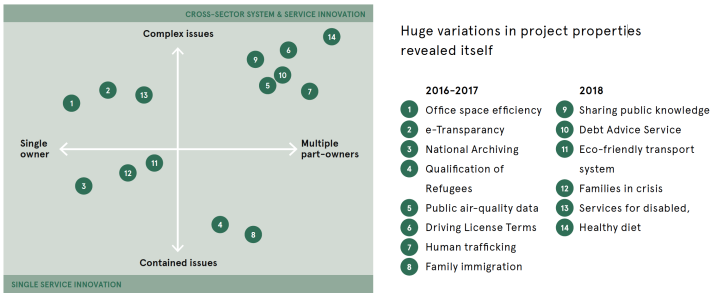

During the initial trial run back in 2016, the Ministry of Modernization demanded that StimuLab’s projects had to deliver results for genuine users by the end of 2017, much in-line with Designit Oslo’s breast cancer project. However, it quickly became apparent that there were huge variations in StimuLab’s project properties, and we realised that project results and impact would vary in time, depending on how complex the challenges were.

StimuLab has chosen to support projects ranging from contained, single-owner services to complex multi-stakeholder challenges. By using a simple chart to arrange projects, we can support dialogue, understanding and assessment of cross-disciplinary needs, relating to their location in the chart. It also creates a better understanding of project properties, ranging from low to high levels of regulatory and cross-sector entanglement and complexity, and what that entails when it comes to the Ministry’s initial anticipation of results.

The breast cancer patients project, for example, would be placed in the bottom left quadrant. It involved a single stakeholder – Oslo University Hospital – and dealt with a contained challenge. The task was complicated, but it was possible to diagnose the problem, reorganise the service, test improvements and achieve results in less than six months.

High-level, complex challenges in the top right quadrant, however, require step-by-step development with multiple stakeholders. Improvements can result in significant socio-economic effects, but progress isn’t as rapid as in a contained service in the bottom left quadrant.

“Management of driving license conditions” is a complex project example, as it dealt with a service involving four government agencies as well as private sector stakeholders. The project began late in 2016 and was run by Halogen Design and Rambøll.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment