Trauma-Responsive Design Research: A New Model for Change

After a 10-year career working with social justice and human rights non-profits, she earned her Master in Social Work in 2010. Rachael worked at Veterans Affairs for nearly seven years, followed by several years in higher education. She has served as an AmeriCorps member, an NGO delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Council, and is currently a Governor-appointed statewide Commissioner with the Serve Illinois Commission on Volunteerism and Community Service.

Rachael has completed graduate work in the Design for Responsible Innovation MFA program at the University of Illinois in Urbana Champaign, focusing on why trauma-responsive methods are relevant and needed in design research and practice.

At this event, she shared a new trauma-responsive design framework and included examples of how this framework allows for emerging practices to be integrated throughout the design process.

Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

To set the tone, Rachael opened up her presentation with an Indigenous land acknowledgment. She paused to enlighten the audience of the historical context of how trauma of political power over others have played in American history, acknowledging her peers, social workers, designers, all those who are descendants of settlers immigrants to the North American continent. She makes a profound point that the land she calls home and where she is based are “stolen lands of the Sioux the Miami Peoria and Kickapoo nations, otherwise known as Urbana, Illinois.”

As she poetically states, “these lands continue to carry their stories and struggles for survival and identity — I find that I have to reflect on the work that I do and how it actively is addressing the histories of people who came far before me — how we can reimagine trauma work how we can we decolonize design and social work practice.”

Tell me your story

“I have training and experience in social work and design,” Rachael shares.

Imagine an object or smell or image you love or hate — just thinking about it could trigger a (traumatic) memory or emotional reaction — the intense thoughts and feelings we attach to a stimulus, a very messy human experience. Of course, not all traumas are felt equally. This naturally leads to philosophical questions or ethics of compassion and empathy. Today, there are plenty of discussions about empathy in design.

What is empathy? How do we create space for radically different responses and viewpoints? Are we simply “doing transactional reporting” when discussing empathy within the context of service design? How are we (or are we) being relational and care-centered while designing for empathy?

Rachael highlights the intersection of social work within the context of design. She says, “I practice being a trauma-responsive designer,” “I wonder about trauma in the context of design a lot.” While she also recognizes influencers, other practitioners in her field, catalysts like UX researcher and social worker Lindsay Cochran, “social workers see the impact of bad design and bad policies.”

Defining Trauma

A recent article in the Atlantic talks about how psychologists and psychiatrists still debate the word’s definition — some feel that the term is used too loosely. Historically, the word “trauma” has been associated with violent experiences, and others argue there is a distinction between mental health and Trauma.

What about collective trauma? Aren’t we all (the world) experiencing a mass trauma from the global COVID-19 pandemic? Could we also think deeper about organizational trauma in the context of design?

You don’t have to experience violence to experience trauma.

To unpack these definitions, Rachael shared an example from Dr. Bruce Perry’s book (co-authored with Oprah) of how a third-grader and a fifth-grader experienced a fire in their grade school. Each student in that context responded differently because of their literal proximity to the event — calling to mind another factor of a trauma response — resiliency.

Time and again, I often revisit the grounding insights of Resmaa Menakem. He is a Minneapolis-based therapist, trauma specialist, and author of My Grandmother’s Hands, a book on the impact of intergenerational and racial trauma. Resmaa, who initiates the wisdom of elders, brings into focus how we carry in our bodies the history and traumas from the vantage point of “race.”

Rachael also offered up Resmaa’s intelligence: “Trauma is a response to anything that’s overwhelming, and that happens too much, too fast, too soon, or too long. It is coupled with a lack of protection or support. It lives in the body, stored as sensation: pain or tension — or is a lack of sensation, like numbness. It does not impact us all in the same way. Context is critically important.”

Defining trauma in the context of design

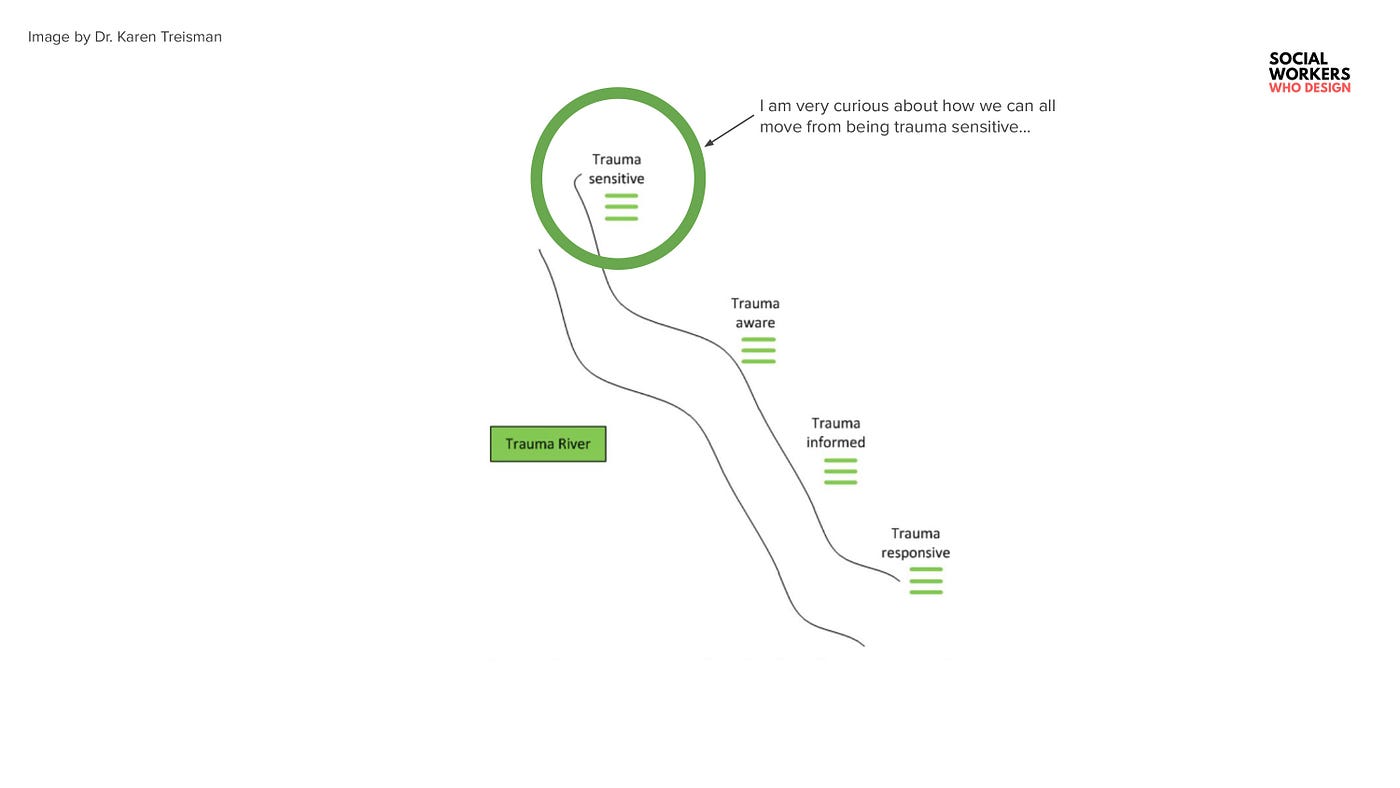

With the assumption that almost everyone here showing up to the evening’s presentation was at least trauma-sensitive, we could ask ourselves, as designers, what can we do to become trauma-informed and trauma-responsive in our practice? Rachael notes, “our identities as designers (and the attachments we have to certain ways of doing design) play a huge role in both how and why we design.”

“How can we design with a humility around trauma — build our trauma knowledge while being care-centered in our work?” These questions are not so simple to answer until (or unless) you have a clear understanding of your values.

What are your values? Expansive core values are the ethos of trauma-responsive design. So are purposeful and careful design. What does it mean to be an ethical social worker and practice ethical and critically conscious design?

But even so, values and purpose only meet the bare minimum without practicing advocacy. Practice advocacy — actively fight to change legislation, understand the interconnection of systems in social work and design spaces, apply systems thinking, and become a systems thinker.

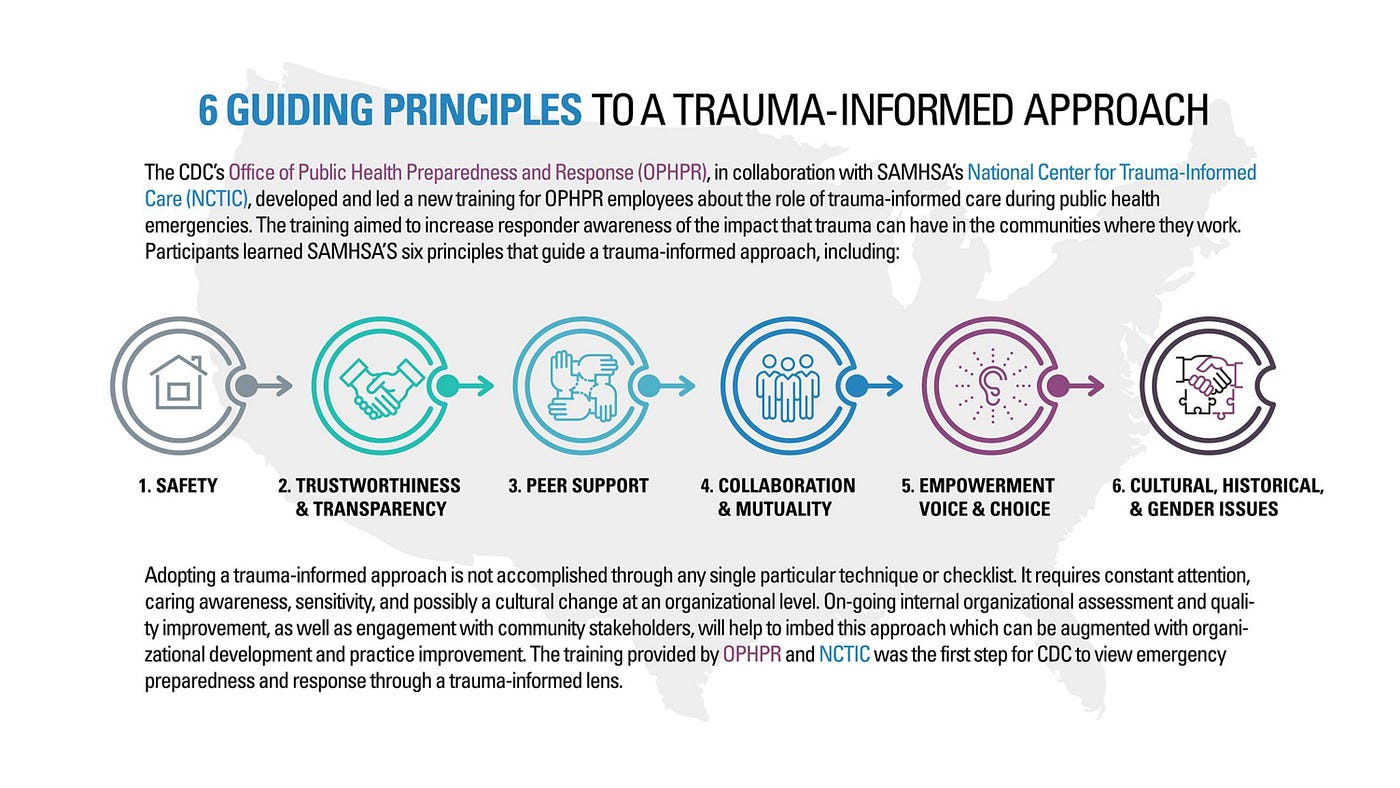

Another way is to build a language around trauma literacy or trauma knowledge. The CDC Office of Public Health has adopted trauma-informed language with six guiding principles that can get incorporated across diverse disciplines and professions. Other adaptations include the Missouri model and the Oregon model.

With this in mind, trauma-informed design is truly a radical participatory human-centered approach to design, as it puts the experiences of all humans up front and center. To build safe experiences or products, we must practice radical participatory design that is trauma-informed.

“What does it mean to be in a community with others?”

How do we individualize interventions with a personalized approach? How do we work around cultural-historical gender issues? Or what does it mean for us in community with others at an organizational level? And while we aspire to provide culturally responsive design services, how will we address structural and systemic barriers, recognize the historical impacts of Trauma, do design differently?

Key takeaways for trauma-informed design practice

Guiding principles to a trauma-informed approach:

- Safety

- Trustworthiness & Transparency

- Peer Support

- Collaboration & Mutuality

- Empowerment, Voice, & Choice

- Cultural, Historical, & Gender Issues

As I write the conclusion of this timely topic, we confront the unimaginable crisis, suffering, and loss occurring to the people and land of Ukraine. The insanity unfolding on our world stage begs the question: What’s the future of community? What shifts the ground of Trauma? As things fall apart all around us, our natural human nobility is tasked to awaken a greater consciousness and primary impulses towards empathy and the heart of humanity.

Recap article by Jeannie Joshi, Creative & Design Director based in New York, NY.

You can find a video recording of this talk on YouTube.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment